There is a direct relationship between the Muslim religion and the practice?

Mother and daughter arrive at a small house in their community. The girl, who has no more than 10 years, clings to the mother's dress with an expression of anxiety. An old lady greets them and forwards them to the backyard. There, the mother points to a lounge chair where the girl should be accommodated. When the old lady returns, brings in her hand a blade used to cut hair - there is a bit of dried blood on one end.

The mother instructs her daughter to lie down. The girl gets nervous and starts to cry, not knowing what to expect. The mother tries to comfort her - unsuccessfully. Once the child's legs are apart, the old lady makes quick movements with the blade, extracting the hood of the clitoris and part of the clitoris itself. The child screams in pain as the mother cries of agony. But it's okay. It's for her own good.

You just read the description of a female genital mutilation (FGM). The tradition mixture mystical and cultural aspects, uniting ideals of purity, modesty and aesthetics, to religious aspirations. The tradition is concentrated in a group of countries stretching from West Africa to Southeast Asia. A Greek papyrus from 163 A.E.C describes the practice, but it is possible that it exists for about 3000 years, as evidenced by an inscription made in an

Egyptian sarcophagus.

In small communities, there is a perception that girls who have undergone FGM are considered more desirable to marry, so mothers fear they will not be able to arrange marriages for daughters who were not mutilated. A girl who can not find a husband is likely to be considered an embarrassment to her family. Also, in regions of Sudan is believed that if the clitoris is not mutilated, it will grow to the size of the neck of a goose, rivaling the husband's penis.

A cultural or religious problem?

In the popular imagination, the tradition is associated with Islam, but there is no consensus within the religion about the practice. Although there is no indication of such in the Quran, those who claim that the practice must be followed by Muslims use excerpts from the Sunnah – set of teachings transmitted in oral form that would be models of behavior for Muslims – as the

dialogue between Muhammad and a woman specialized in this type of mutilation:

This woman, known as an exciser of female slaves, was one of a group of women who had immigrated with Mohammed. Having seen her, Mohammed asked her if she kept practicing her profession. She answered affirmatively adding: "unless it is forbidden and you order me to stop doing it". Mohammed replied: "Yes, it is allowed. Come closer so I can teach you: if you cut, do not overdo it (la tanhaki), because it brings more radiance to the face (ashraq) and it is more pleasant (ahza) for the husband"

The Sunnah is a series of parables about the life of the Prophet Muhammad that not necessarily should be followed, despite being quite recommended. The interpretation changes according to society and time, so adherence and reception to traditions based on the Sunnah is something that differs greatly between Muslim communities.

The mainstream understanding between Muslim religious leaders is to refuse to condemn female genital mutilation, like Ahmed Al Khalili, Great Mufi of Oman, who

stated:

Even though its not an operation you must perform on women, we can’t describe it as a crime against women or as a violation of women’s rights.

Also, the late Lebanese Ayatollah. Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah

stated:

Circumcision of women [FGM] is not an Islamic rule or permission; rather it

was an Arab ritual before Islam. There are many Hadiths that connote the

negative attitude of Islam as to this ritual. However, Islam did not

forbid it at that time because it was not possible to suddenly forbid a

ritual with strong roots in Arabic culture; rather it preferred to

gradually express its negative opinions. This is how Islam treated

slavery as well.

On the other hand, the Ayatollah Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, considered the practice retrograde, "because social norms have changed today, this action would not be acceptable as many other topics that your sentences have been changed due to circumstances and facts",

stated.

Although components of Muslim culture encourage female genital mutilation (or fail to condemn it), Christian groups in Africa and Middle East also cultivate the practice. In Egypt, where 87% of women suffered mutilation, both Muslims as Coptic Christians are conniving.

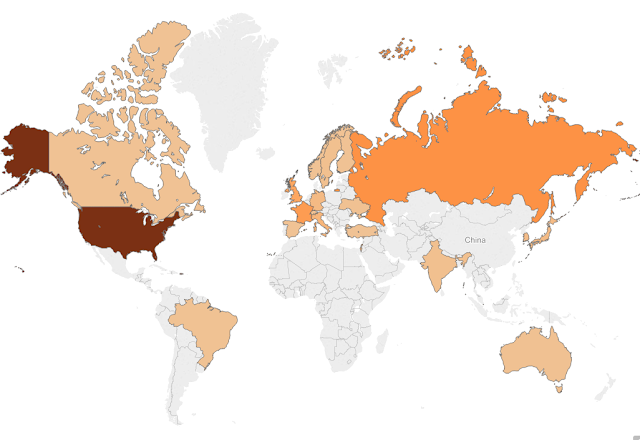

There are countries where the number of cases of mutilations does not correlates with the proportion of the population that is Muslim. In Iraq, where Muslims represent 99% of the population, only 8% of all women have suffered genital mutilation. In Eritrea, where 83% of the female population was victim of mutilation, Muslims represent 37% of the total population.

Incidence from East to West

In Asia, female genital mutilation is a problem unique of Muslim communities. In Indonesia, the Muslim community represents 87.2% of the total population, and 85% of the female population was subjected to mutilation. In Malaysia, where Muslims account for 63.7% of the population, 57% of all women were victims of mutilation.

Although there is no reliable data for several countries in Asia, there are records of female genital mutilation in Muslim communities in India (14.4% of the population is Muslim), Afghanistan (99%), Brunei (75.1%), Maldives (98.4%), Pakistan (96.4%), Philippines (5.5%), Singapore (14.3%), Sri Lanka (9.8%), Tajikistan (96.7%) and Thailand (5.5%).

In the West, the practice was used during the 19 century in the United States of America and Europe, as a way to contain excessive sexual desire in women. With the waves of migration of the population from Middle East to European countries, sporadic cases were made public in immigrant communities in France (14.4% of the population is Muslim), Germany (5.8%), Italy (3.7%), Sweden (4.6%), United Kingdom (4.8%), United States of America (<1%) and Canada (2.1%).

Resistance to eradicate the problem

The eradication of the problem requires systemic action, facing the practice on religious, cultural and governmental levels.

Muslim leaders stand openly against FGM are still a minority. Ali Gomar, the Grand Mufi of Egypt,

stated:

The practice must be stopped in support of one of the highest values of Islam, namely to do no harm to another – in accordance with the commandment of the Prophet Mohammed “Accept no harm and do no harm to another".

Cultural aspects also need to be addressed, because, as said before, social rites are tied to female genital mutilation. The project

Girls not Brides understands that the habit of marrying their mutilated daughters even prior to adolescence is a way open possibilities and protects them from social sanctions. So those who reproduce this tradition are being influenced by projects like

The Grandmother Project, which persuades grandparents to influence members of your community to put an end to these practices.

Despite international pressure to eradicate the practice, Arab Governments refuse to deal with the problem. Fran Hosken, activist, founder of the Women's International Network News and author of pioneering research in the area, especially

The Hosken Report, described the responsible authorities of the countries where female genital mutilation is concentrated as accomplices of a cartel of silence, in which participants enjoy much influence at the UN and show no interest in solving social problems.